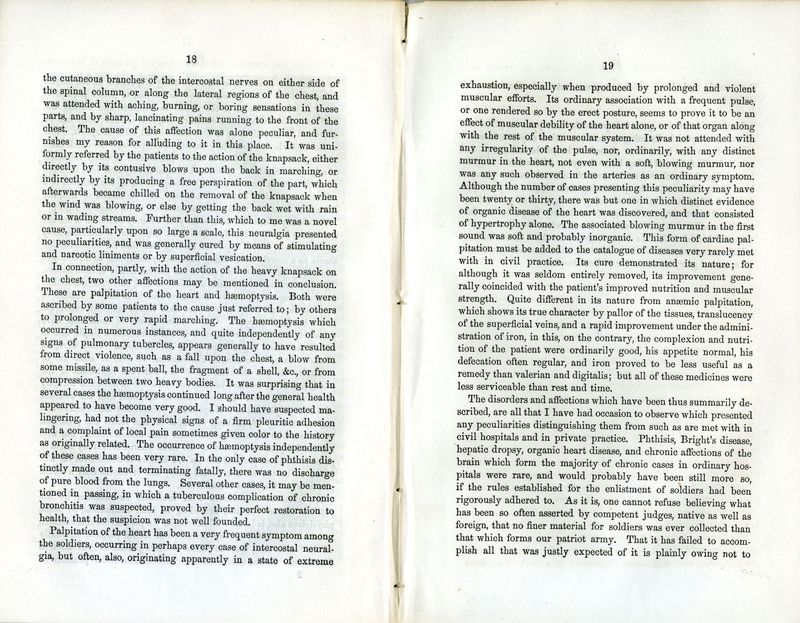

3

Alfred Stillé (1813-1900)

Address before the Philadelphia County Medical Society, Delivered February 11, 1863

(Philadelphia : Collins, 1863).

From the collections of the Boston Medical Library.

Following the observations of Civil War soldiers treated by Alfred Stillé (“This form of cardiac palpitation must be added to the catalogue of diseases very rarely met with in civil practice”) and Henry Hartshorne and cases he had himself seen in military hospitals, Philadelphia physician J. M. Da Costa identified a cardiac phenomenon in soldiers which he termed “irritable heart.”

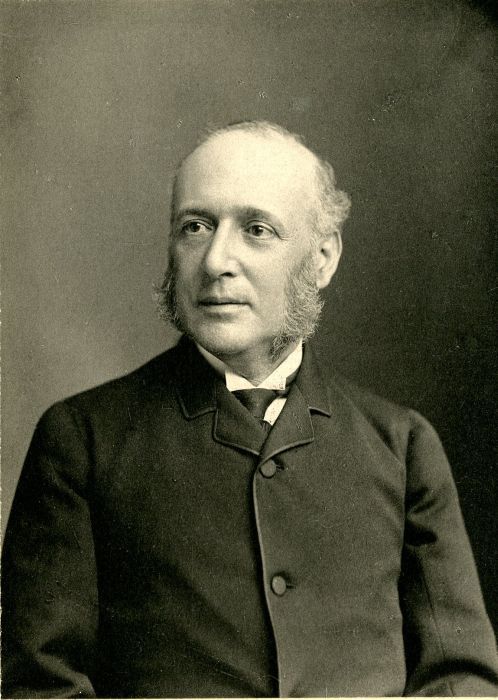

Photograph of Jacob Mendes Da Costa, circa 1880.

From the collections of the Boston Medical Library.

Da Costa made a brief mention of this in his 1864 textbook, Medical Diagnosis, and then subsequently published this article describing the phenomenon at greater length:

"He rejoined, after a short stay in hospital, his command, and again underwent the exertions of a soldier’s life. He soon noticed that he could not bear them as formerly; he got out of breath, could not keep up with his comrades, was annoyed with dizziness and palpitation, and with pain in the chest; his accoutrements oppressed him, and all this though he appeared well and healthy…. The case might go on for a long time, and the patient, after having been the round of hospitals, would be discharged, or, as unfit for active duty, placed in the Invalid Corps."

This phenomenon, also known as “soldier’s heart” or “Da Costa syndrome”, is now thought to be an anxiety disorder—a form of post-traumatic stress.

Charles Beneulyn Johnson (1843- 1928)

Muskets and Medicine, or, Army Life in the Sixties

(Philadelphia : F.A. Davis Co., ; London : S. Phillips, 1917).

From the collections of the Library of Harvard Medical School.

Charles B. Johnson served with the 130th and 77th Illinois regiments and became a physician after the war. Late in life, he published this memoir of his experiences with particular attention to medical care and diseases of soldiers during the Civil War. Johnson himself was troubled with chronic diarrhea over a six-year period and here describes some of the similar afflictions suffered by his comrades. Diarrhea and dysentery were the most common illnesses afflicting Civil War combatants, followed by typhoid fever, pneumonia, and malaria.

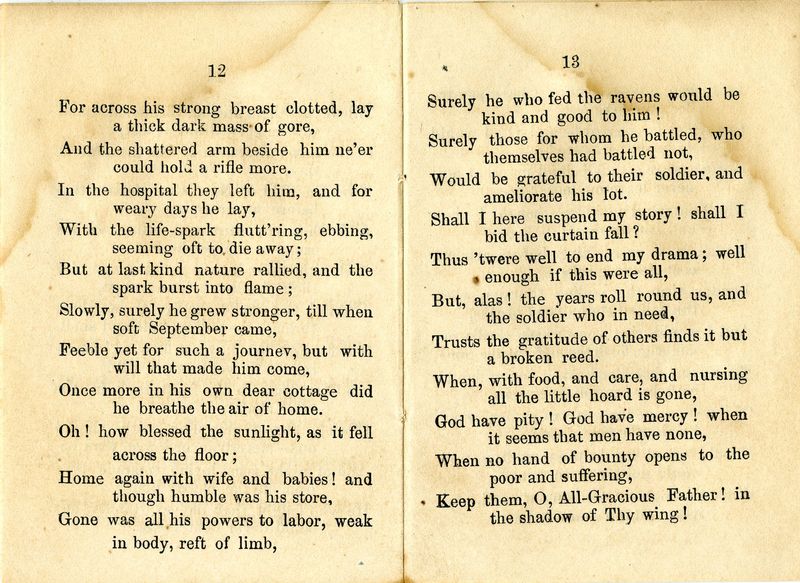

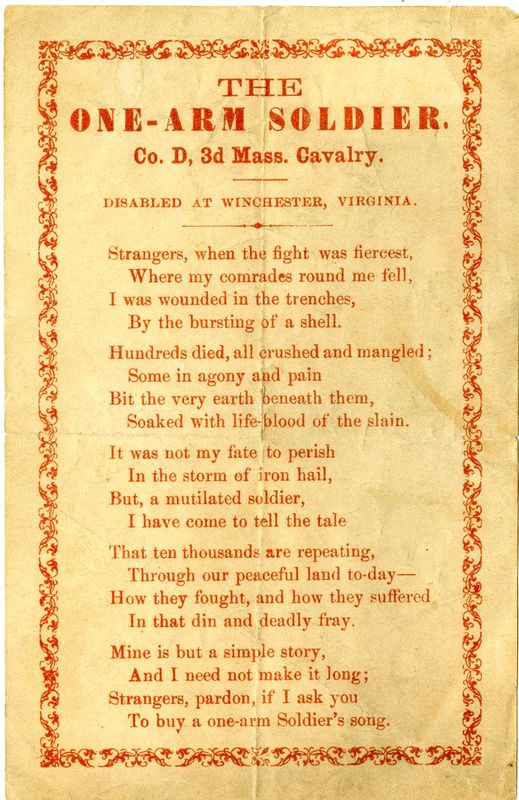

The Empty Sleeve, or, Soldier's Appeal

(Boston : John Smith, 1874).

Purchased for the Library of Harvard Medical School, 2005.

This pamphlet and the following two broadsides are examples of postwar mendicant literature—items printed and sold for the support of their authors—and illustrate some of the hardships faced by soldiers in battle who became disabled veterans in later life.

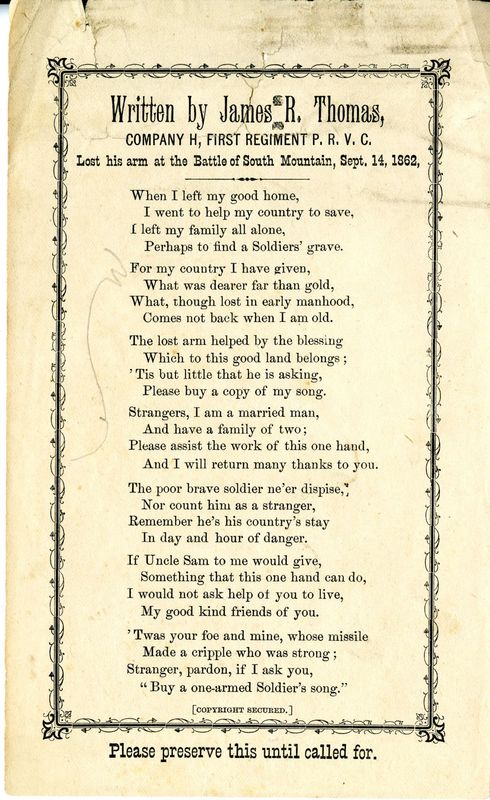

James R. Thomas

When I Left My Good Home [S.l. : s.n., ca. 1862].

Purchased for the Library of Harvard Medical School, 2005.

The two broadside poems (see "The one-arm soldier" below) are variants on the same idea of the disabled man’s empty sleeve, and the final verse (“Strangers, pardon, if I ask you / to buy a one-arm Soldier’s song”) is common to both.

The One-Arm Soldier : Co. D, 3d Mass. Cavalry, Disabled at Winchester, Virginia

[S.l. : s.n., ca. 1870?].

Purchased for the Library of Harvard Medical School, 2005.

“The one-arm soldier,” poem, appears, with minor changes, in a number of different broadsides from the period, and is associated, variously, with John Williams, who was wounded at Winchester, George M. Reed, wounded at Shiloh, Henry H. Meacham, and Harry Gilmore, a “one-armed boy”, wounded at Petersburg—all may have used and sold a common poem, rather than writing it.

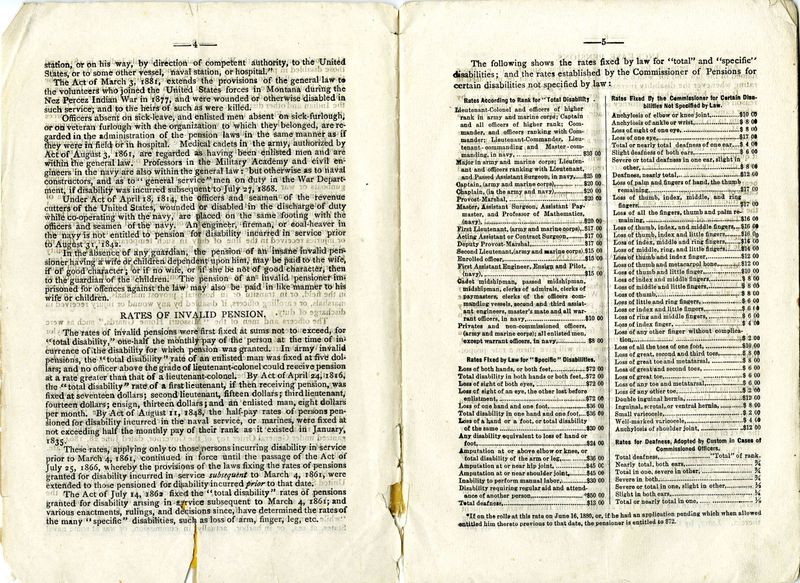

The Soldiers' Manual : a Hand Book of Useful and Reliable Information, Showing Who Are Entitled to Pensions, Increase, Bounty, Pay, etc. ...

(Cleveland, Ohio : Milo B. Stevens & Company, [1888]).

Gift of William B. Rogers to the Library of Harvard Medical School, 1981.

The legal firm of Milo B. Stevens & Company was established in 1864 and specialized in military pension claims for veterans and their families. The firm had offices in Washington, Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago. This edition of its publication, The Soldiers’ Manual, includes a table of compensation for various levels of disability.

While the last confirmed Civil War veterans, Albert Henry Woolson of the Union Army and Pleasant Crump of the Confederate, died in the 1950s, the last Union war widow, Getrude Janeway, only died in 2003 and the last Confederate widows, Alberta Martin and Maudie Hopkins, died in 2004 and 2008.

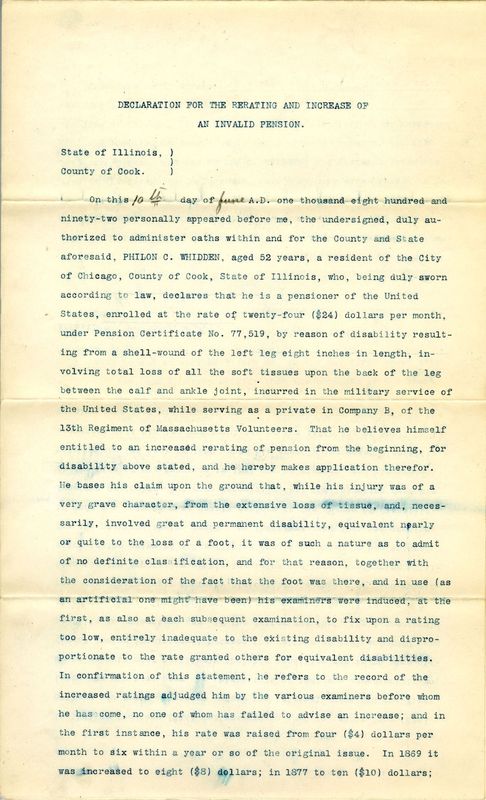

Declaration for the Rerating and Increase of an Invalid Pension for Philon C. Whidden, June 10, 1892.

Gift of William B. Rogers to the Library of Harvard Medical School, 1981.

His medical studies interrupted due to lack of funds, Philon Currier Whidden (1839-1900) enlisted as a private with the 4th Battalion of Rifles of the 12th Massachusetts Volunteers in June, 1861. He was severely wounded in the left leg at Antietam in September, 1862. From his own account, Whidden states, “My slight medical knowledge enabled me to make such a representation of my physical condition, strength of constitution, etc., as to secure a more than ordinarily careful consideration of my case by the surgeons and saved me from the speedy amputation which the nature and severity of the wound seemed to demand.” Whidden was subsequently appointed acting assistant surgeon in the U.S. Navy and served to the end of the war. He then resumed his studies at Harvard, received a medical degree in 1866, and went into practice in Chicago.

By the late 1880s, Whidden’s condition had deteriorated, and “preferring mutilation to the crippled and suffering condition which he had endured for the previous twelve years,“ he submitted to an amputation of his lower leg in April, 1891. This document forms part of his application for an increase in his military pension due to the amputation and need for an artificial limb.