The Extraordinary

Although the majority of the LEAN collection is comprised of common medical instruments, there were a few unusual finds amongst the boxes. Some of these were items that had no medical context and had likely made their way into the collection by accident. Some, however, were extraordinary objects that relate to important moments in the history of medicine.

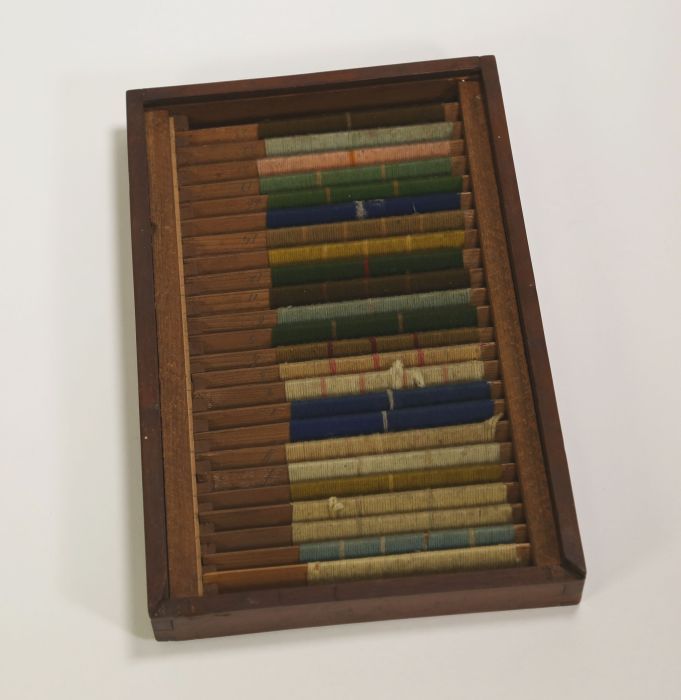

Benjamin Joy (B. Joy) Jeffries (1833-1915) was a 19th-century ophthalmologist. His work focused primarily on the causes and identification of color blindness. At the time that Jeffries was working, color blindness was not commonly identified. It was a serious hazard for railroad workers and people in similar occupations. A misinterpreted signal due to not seeing the right colors could result in a dangerous or even deadly situation. Jeffries’ work on the subject and advocacy for testing resulted in a much deeper understanding of color blindness and a safer railroad system.

The test shown here was developed in 1879 by the ophthalmologist Franciscus Cornelis (F. C.) Donders (1818-1889). This test—which Jeffries described in his book Color Blindness: Its Dangers and Detection—involved a fairly simple procedure that wouldn’t have needed the complicated equipment like colored lights and spinning disks that some other methods required. Jeffries favored another test called Holmgren's Method, but likely used this test on many of his patients.

At the turn of the century, Dr. James Mackenzie (1853-1925) developed the first ink-writing polygraph. This machine had nothing to do with detecting lies, but was created to diagnose irregular heartbeat. This device was much simpler than the polygraph machine that most people are familiar with today, as it was only tracking heart rate, but it works in much the same way. It features two rubber tambours, one of which was attached to a vein in the neck and the other to the wrist. These tambours would move with the patient’s pulse, and the waves of this movement would be sent down rubber tubing to two recording arms with needles. Then, the needles would record the pulse as a continuous ink-line on paper, which showed the pattern of the patient's heartbeat.

At the time that Mackenzie introduced the machine, there wasn’t an effective way for physicians to track the pattern of a patient’s heartbeat. The Electrocardiogram machine (or EKG) soon became widely available, making the Mackenzie polygraph a short but important segment of the history of cardiology.

Smallpox was a viral disease that caused a skin rash, resulting in permanent scarring and sometimes loss of vision. The disease had a mortality rate of 30%, with a higher rate amongst infants. Edward Jenner developed a vaccine to protect against smallpox in 1798. The vaccination was given using a bifurcated needle: a short metal rod with a flat, pronged head designed to hold a single dose of the vaccine. As vaccination rates increased amongst developed countries, the disease rate lowered dramatically, but smallpox still proliferated in areas where the vaccine was not easily available. Because of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) determined that smallpox was a good candidate for eradication.

In 1966, D.A. Henderson became the head of the project. At this time, smallpox was endemic in 33 countries, with an estimated 15 million cases every year. Henderson believed that in order to eradicate the disease, the focus had to be on the number of individuals contracting the disease rather than the number of vaccines given. This led him to coin the phrase “Target Zero” because the goal of the campaign was to see zero cases of smallpox. When the eradication project was close to complete, Henderson and his daughter created these pins—a bifurcated needle twisted into a circle to represent Target Zero—and awarded them to everyone who helped with the project, along with admittance to the Order of the Bifurcated Needle.

The last known case of smallpox was reported in 1977, and WHO declared the disease eradicated in 1980.

In 1796, the physician Elisha Perkins began selling metallic tractors that he claimed could cure many diseases, including rheumatism, inflammation, and epilepsy, simply by touching them to the skin. The tractors became incredibly popular throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Although the tractors had critics, they were endorsed by many physicians and prominent members of society, including George Washington. The tractors were sold for $25 a pair: close to a $500 value today.

Many scientists and doctors, however, felt that these were quack devices, and decided to test them. Multiple English physicians conducted tests in which some of their patients were treated with genuine Perkins tractors, and some were treated with instruments made of other materials. These physicians all found that all materials were equally effective, so long as the patient believed that they were being treated with genuine Perkins tractors. These were likely some of the earliest experiments into what we know today as the placebo effect: the idea that a person’s body can have a response to a treatment simply because they believe that it will work. Once these results were published, the tractors became widely ridiculed and fell out of fashion.