1868-1898

The death toll of the Civil War was enormous and unprecedented for its time. But even those soldiers who survived often paid a heavy price in wounds, injuries, and lost limbs. After the war, the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office began to collect, document, and describe some of the more notable cases and published these patient histories as Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens Taken at the Army Medical Museum (Washington : Government Printing Office, 1865-1868).

This publication contains photographs and case histories of a number of Civil War soldiers, particularly amputees. These early images of war’s aftermath can be graphic and disturbing, but the cases also illustrate the development of surgical techniques and innovative prosthetic devices. Many of the images employ elaborate furniture and mirrors, displaying a high degree of artistry and fascination with the still-new technology of photography as well.

Although he never practiced as a physician, William James—philosopher and psychologist best known for The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902)—received a degree from Harvard Medical School in 1869 and taught physiology during the 1870s. This notebook was used by James as a Harvard student when he attended the lectures of Henry J. Bigelow, Henry I. Bowditch, and other members of the medical faculty. James Jackson Putnam, who would become one of William James’s close friends, was also a medical student at this time.

In a letter to his sister, Alice, from this period, James claimed he had just attended a lecture "which I could not understand a word of, but rather enjoyed the sensation of listening to for an hour." Here William James—despite his wandering attention—has taken notes on the lectures of Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard on writer’s palsy and other diseases of the nervous system.

This photograph, one of a set of five taken by Washington photographer C. M. Bell after the autopsy on President Garfield’s body, shows the assassin’s bullet hole in his spine. The bullet fractured the 11th and 12th ribs and passed through the vertebrae from the right side to the left. The autopsy revealed that the immediate cause of Garfield’s death was a ruptured aneurysm in the splenic artery—damage caused by either the bullet or surgical probes of the physicians attempting to remove it.

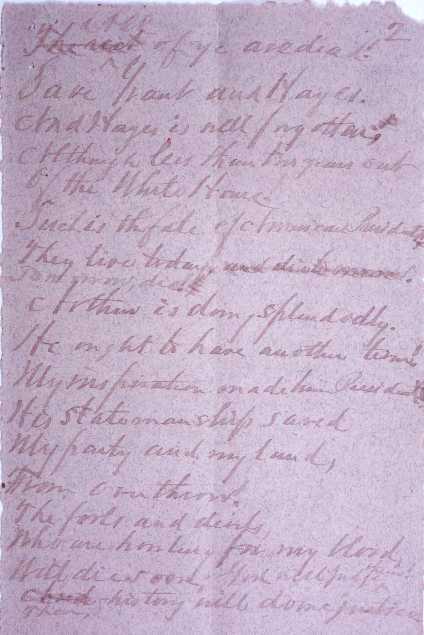

This is a leaf from a poem by Charles Julius Guiteau, the assassin of President James A. Garfield, written in prison shortly before his execution. On July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield in the arm and in the back, maintaining this was a "political necessity" and that Chester Alan Arthur should be president. After Garfield’s death on September 19, a sensational trial—turning on an insanity defense—ensued. Although some argued that Guiteau was clearly insane and should not be held accountable for his actions, he was convicted and executed on June 30, 1882. This poem is part of a small collection of letters, newspaper clippings, a diary, and other manuscript material assembled by the Reverend William Watkin Hicks of Washington, D.C. Hicks served as Charles Guiteau’s spiritual advisor in prison and was a staunch opponent of his execution.

In 1894, Harvey Williams Cushing and Ernest Amory Codman (1869-1940), both junior house pupils at Massachusetts General Hospital, made a bet to see who could develop better control over the administration of surgical anesthesia and thereby limit the distress—and even accidental death—of patients during operations. The two young physicians each devised charts to graph temperature, pulse, and respiration of their patients while anesthetized. This volume contains the original ether charts of both Codman and Cushing.

Thirty years later, Dr. Cushing could not recall who won the wager, but maintained both he and Dr. Codman became more skillful in their work because of the care and close attention paid to the condition of anesthetized patients. These charts—precursors of the electronic monitoring systems common today—are the earliest examples of meticulous documentation of a patient’s vital signs, and their development is one of the major American contributions to surgical technique.

These two radiographic prints are not only specimens of some of the earliest X-ray images but also particularly notable for their subjects and the clarity of the bones, cufflink, and jewelry of the imperial couple. While the diagnostic value of W. C. Röntgen’s discovery a few years earlier was immediately apparent to physicians, this technology also entertained the public—even the royal public—with its novelty.

The donor of these two photographs received them from the wife of Dr. H. H. Horne in Lapland after the 1917 Russian Revolution. At the Czar’s request, Dr. Horne had brought his X-ray apparatus to the palace at St. Petersburg in the winter of 1898. During the photographic session, according to Mrs. Horne, the equipment overloaded the palace’s electrical system, and she inadvertently bumped into the Czar in the darkness.