"Turned Over Like a Flapjack"

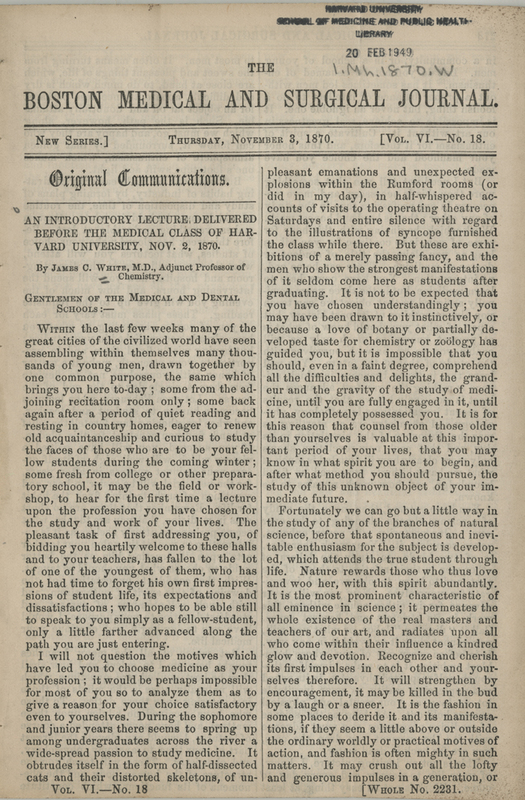

Despite the Medical School's array of courses and renowned faculty members, the students themselves in the mid-19th century were often poorly trained. Few of the matriculants had formal college degrees upon entering the school, the required course of study was short, and the medical examinations at the end—termed "ridiculously easy" by Professor James C. White (1833-1916)—were haphazard. As early as the mid-1860s, White called for higher standards in preliminary education, greater emphasis on the sciences, and an enhancement of the training of American physicians to match the standards of European schools. But it was only the advent of Harvard's president, Charles William Eliot (1834-1926), in 1869 which brought about a complete revolution in the medical curriculum. Eliot himself stated that, "An American physician or surgeon may be, and often is, a coarse and uncultivated person, devoid of intellectual interests outside of his calling, and quite unable to either speak or write his mother tongue with accuracy…. Until the reformation of the School in 1870-71, the medical students were noticeably inferior in bearing, manners and discipline to the students of other departments."

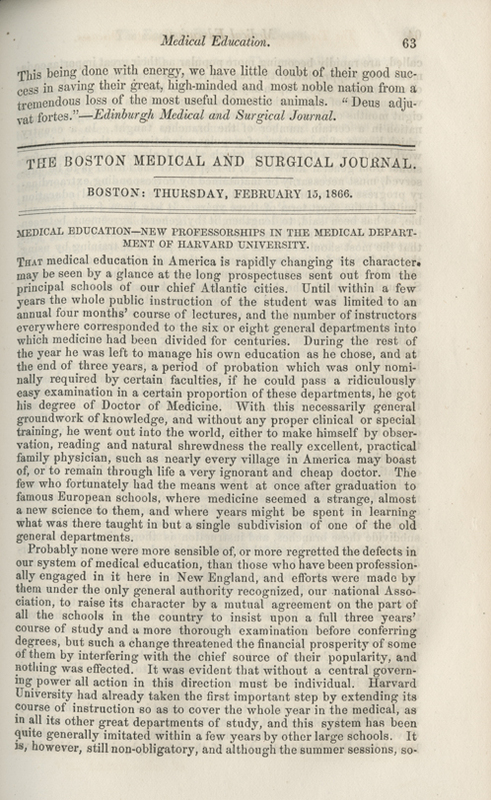

The challenge to reform American medical education and bring it closer to the higher standards current in Europe started even before this editorial appeared in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. James C. White, a member of the faculty of the Medical School, decried educational standards, saying, “… if [a student] could pass a ridiculously easy examination … he got his degree of Doctor of Medicine. With this necessarily general groundwork of knowledge, and without any proper clinical or special training, he went out into the world, either to make himself by observation, reading and natural shrewdness the really excellent, practical family physician, such as nearly every village in America may boast of, or to remain through life a very ignorant and cheap doctor.”

White called for a general full year of medical instruction, an array of examinations, and an increase in the number of faculty members. Harvard, by incorporating the summer courses of the Tremont Street Medical School in 1858, had already provided for an increase in the length of the curriculum, had instituted more rigorous exams during the Civil War, and, as White announces in this article, had just created a chair in comparative anatomy and made assistant and adjunct appointments in physiology and surgery.

Introductory lectures to new medical students were customary at the opening of each academic year and often printed in pamphlet form or, as here, in the pages of a medical journal. James C. White cautions the students against specializing too early and stresses greater preparation, a longer course of study, and rigorous examinations. He concedes, however, that true reform, even at Harvard, would come only slowly and at some cost: “An analysis of the list of those who attended lectures last year shows that of 276 students but 62 had received a previous collegiate education… We may conclude then that such a reform would inevitably be followed by the immediate loss of two thirds of its present number of students, by an equivalent crippling of its material resources, and the sacrifice of the prestige of a large school.”

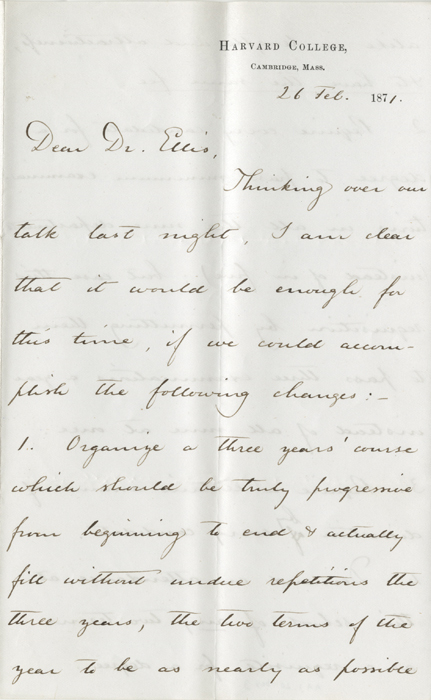

In this letter to Calvin Ellis, the dean of Harvard Medical School, President Eliot outlines several key factors in his proposed educational reforms: a three-year course sequence; examinations, partly written, in each department; familiarity with dissection; and attendance for at least two terms. These changes were all in place by the opening of the term in the fall of 1871.

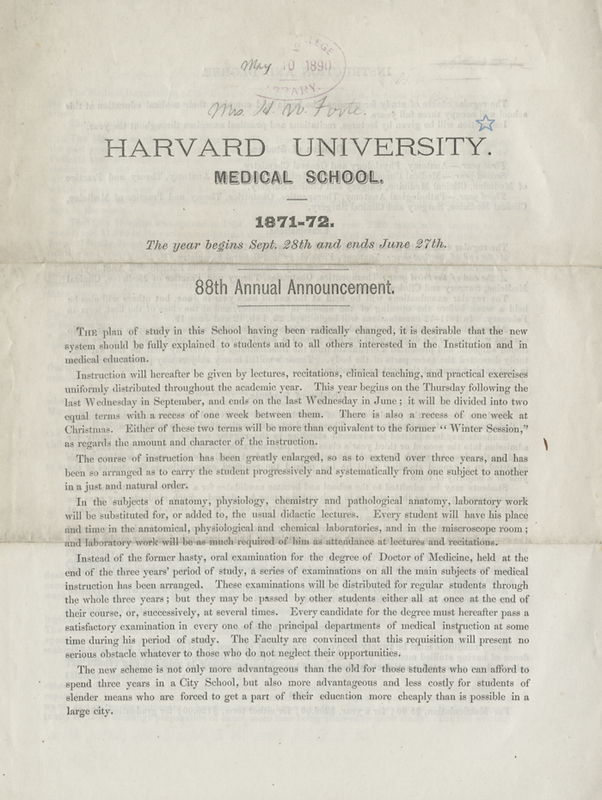

This broadside issued following President Charles W. Eliot's educational reforms outlines the revolution in Harvard's medical curriculum. The academic year now begins earlier, three years' study is required, and the importance of practical and laboratory work over formal lectures is emphasized.

President Eliot faced resistance from the faculty but ultimately managed to institute a new set of statutes for the Medical School in 1870, insisting on more stringent entrance requirements. He also increased the size of the faculty and moved them onto salaries rather than per course fees, extended the medical course to three years with examinations throughout, and even began the academic year in September rather than November. Oliver Wendell Holmes said, of these changes, "Our new President, Eliot, has turned the whole University over like a flapjack. There never was such a bouleversement as that in our Medical Faculty." Eliot also presided over meetings of the Medical Faculty and brought the Medical School more closely under the guidance of the University, making faculty appointments subject to the Harvard Corporation, rather than just the Medical Faculty.

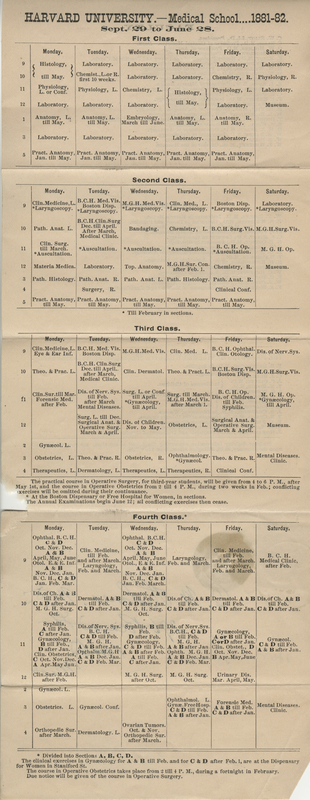

As part of the reform movement at Harvard, the recommended medical degree course was extended from three years to four in 1880. Students could still finish the requirements for an M.D. in three years, and anyone who completed a fourth was granted the degree of M.D. cum laude. The option to pursue a three-year course was still available until 1892 when a four-year course of study became a requirement.

This schedule from the 1881-1882 academic session outlines a student’s typical week as well as the curriculum and course of instruction.