Page 2

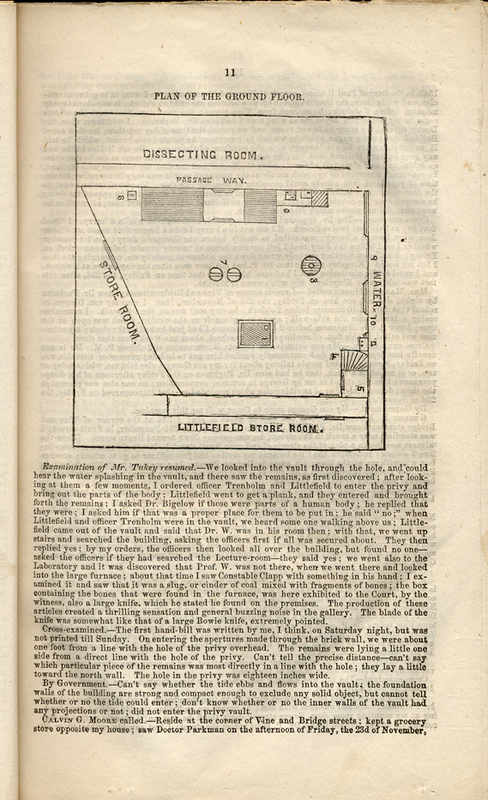

While few early photographs exist of the Harvard Medical School building on North Grove Street, considerable information about the structure and its interior can be found, ironically, in the published transcripts of the 1850 murder trial of John W. Webster (1793-1850). Dr. George Parkman, a noted Boston physician and Harvard benefactor, disappeared on November 23, 1849, and a subsequent search of the premises of the Medical School revealed parts of a human body—including artificial teeth—in the laboratory of Dr. John W. Webster, Harvard’s Erving Professor of Chemistry. Webster was convicted of the murder of Parkman and executed on August 30, 1850.

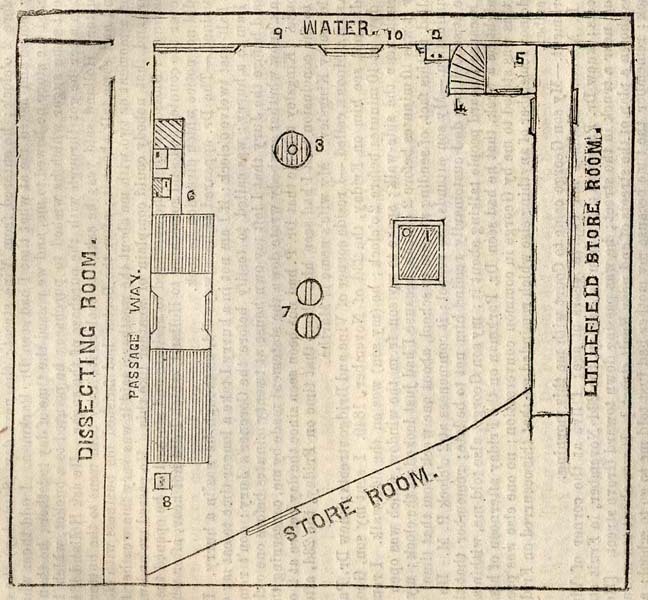

These two trial transcripts with drawings of the facility give some idea of the small size of Harvard Medical School at this time. The plan of Dr. Webster’s laboratory shows the locations of the tea-chest, furnace, and privy where the remains of George Parkman were discovered.

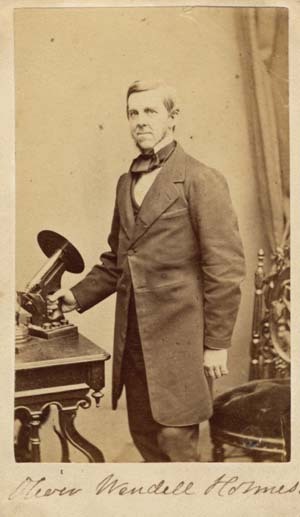

Oliver Wendell Holmes began to offer instruction in microscopic anatomy at the Tremont Street Medical School in the late 1840s and was offering practical instruction in the use of the microscope to medical students at Harvard by 1855. He was one of the first Americans to introduce microscopy into a medical curriculum.

In an address to the Boston Microscopical Society in 1877, Dr. Holmes said, “My dealing with the instrument has been principally as a teacher, and not of microscopy as a specialty, but as a fractional portion of long-extended courses on anatomy, delivered to large classes. The most I could hope for was to teach them the rudiments of histology, and more especially to give them knowledge enough to make them wish for more. I have therefore aimed at having perfectly and easily manageable instruments, at selecting the more important and interesting objects, and at making everything as plain as practicable, knowing well that if a mistake in looking through a microscope is within the bounds of possibility, the young student will be certain to make it.”

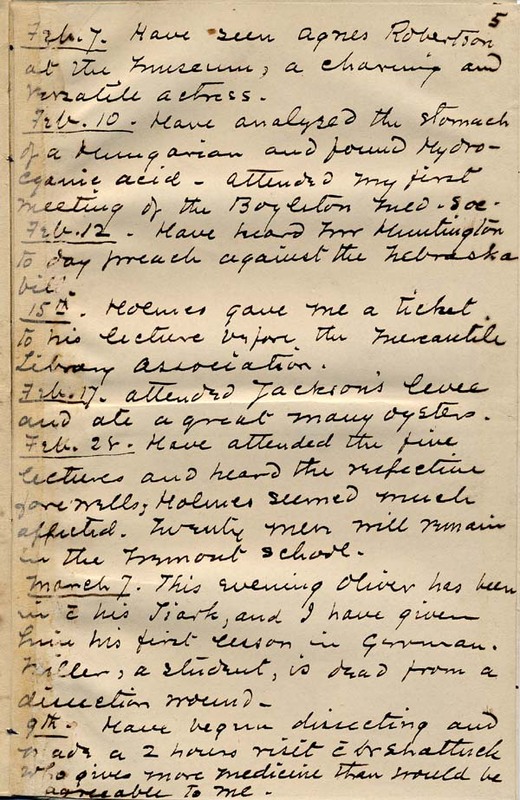

Harvard professor James C. White was also a graduate of the Medical School. In 1898, at a meeting of the Vienna Club, he read these extracts from a diary he kept while at Harvard from 1853 until 1855. His entry for October 8, 1853, notes, “Many operations at hosp[ital] as one of the p[a]t[ient]s refused to take ether. Saw the difference in an operation before & after discovery of ether.” The first public surgical operations using ether anesthesia had been performed at Massachusetts General Hospital just seven years before.

An invitation to the Harvard Medical School Commencement in the North Grove Street building in 1857.

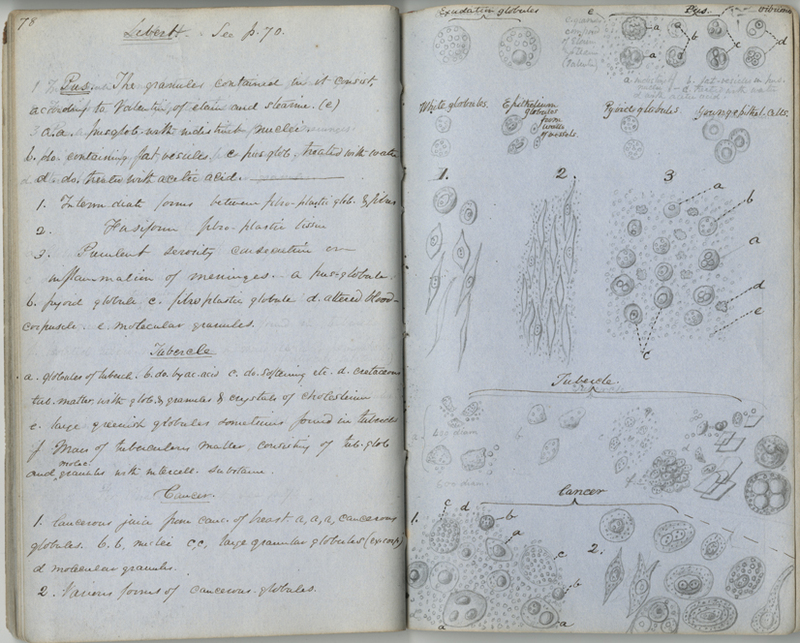

This volume records Oliver Wendell Holmes’ notes for his anatomical lectures at Harvard during the 1850-1851 academic session. The notebook also includes a series of microscopic demonstrations made in April and May, 1851.

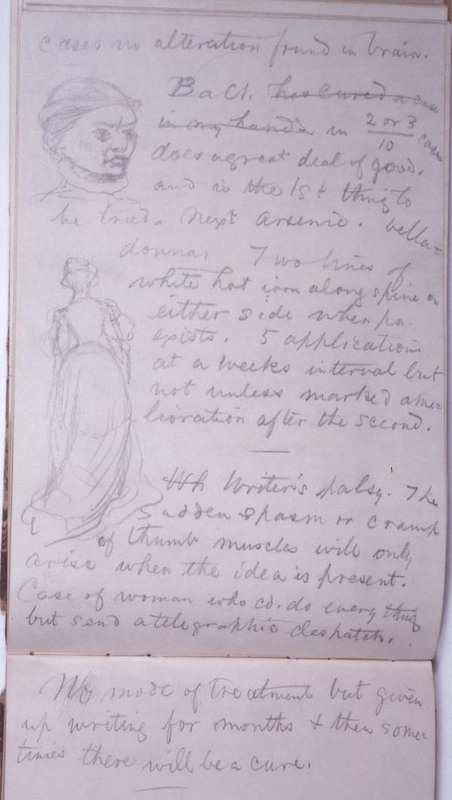

Although he never practiced as a physician, William James—philosopher and psychologist best known for The Varieties of Religious Experience(1902)—received a degree from Harvard Medical School in 1869 and taught physiology during the 1870s. This notebook was used by James as a Harvard student just after the Civil War, as he attended the lectures of Henry J. Bigelow, Henry I. Bowditch, and other members of the medical faculty.

In a letter from this period to his sister, Alice, James claimed he had just attended a lecture “which I could not understand a word of, but rather enjoyed the sensation of listening to for an hour.” Here William James—though his attention is clearly wandering—has taken notes on the lectures of Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard on writer’s palsy and other diseases of the nervous system.