Prisons and Prisoners-of-War

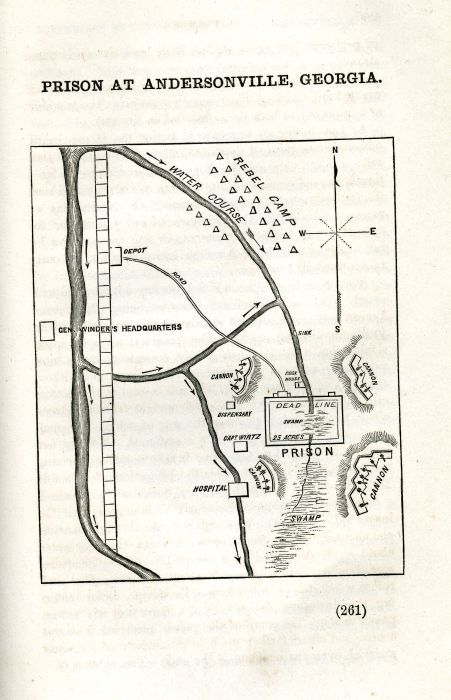

"Prison at Andersonville, Georgia"

United States Sanitary Commission

Narrative of Privations and Sufferings of United States Officers and Soldiers while Prisoners of War in the Hands of the Rebel Authorities : Being the Report of the Commission of Inquiry, Appointed by the United States Sanitary Commission

(Philadelphia : Printed for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, by King & Baird, 1864).

From the collections of the Boston Medical Library.

In May 1864, Dr. Valentine Mott and others members of the Sanitary Commission were charged with investigating accounts of brutal treatment of Union soldiers in Libby, Belle Isle, Andersonville, and other Confederate prisons. The Commission’s report includes testimonies of officers and privates, medical personnel, and Dorothea Lynde Dix, the Union’s Superintendent of Army Nurses. One of the privates, Prescott Tracy of the New York Volunteers, described conditions at Andersonville.

"Wells had been dug, but the water either proved so productive of diarrhea, or so limited in quantity that they were of no general use. The cook-house was situated on the stream just outside the stockade, and its refuse of decaying offal was thrown into the water, a greasy coating covering much of the surface. To these was added the daily large amount of base matter from the camp itself …. One side of the swamp was naturally used as a sink, the men usually going out some distance into the water. Under the summer sun this place early became corruption too vile for description, the men breeding disgusting life, so that the surface of the water moved as with a gentle breeze. The new-comers, on reaching this, would exclaim: “Is this hell?” yet they soon would become callous, and enter unmoved the horrible rottenness."

Some 15,000 prisoners died at Andersonville. The map displayed shows the layout of the prison.

"Artificial limbs removed"

Photograph of J. W. January, circa 1880.

From the collections of the Boston Medical Library.

John Wales January enlisted in Company B of the 14th Illinois Cavalry and was captured in July, 1864. The reverse of the original print of this photograph gives January’s account of his sufferings as a prisoner of war and the amputation of his own feet.

January married in 1869, fathered several children, and died in South Dakota in 1906.

Click on the image at left to read a transcription of his account recorded on the reverse.

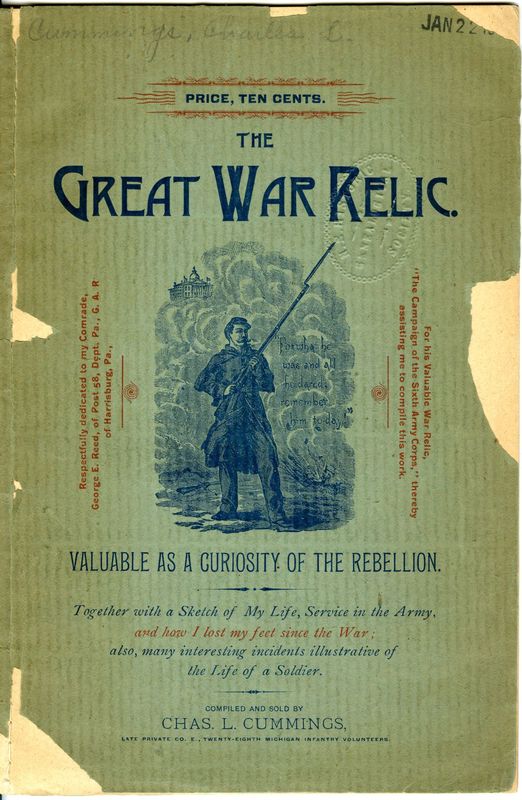

Charles L. Cummings (b. 1848)

The Great War Relic ... Valuable as a Curiosity of the Rebellion. Together with a Sketch of My Life, Service in the Army, and How I Lost My Feet since the War; also, Many Interesting Incidents Illustrative of the Life of a Soldier

[Harrisburg, Pa,: Meyers Printing and Publishing House, 1891?].

Purchased for the Library of Harvard Medical School, 2005.

Remarkable as the story of John Wales January appears, a portion of this pamphlet of essays and poems sold by Charles L. Cummings refutes the tale. George E. Reed, a private in the 95th Pennsylvania Volunteers and Chief Nurse at the Gangrene Hospital in Florence Prison, amputated both of January’s feet and buried them, publishing his own account of the case.

The Empty Sleeve : or, the Life and Hardships of Henry H. Meacham, in the Union Army,

(Springfield, Mass. : sold for the benefit of the author, [1869?]).

Purchased for the Library of Harvard Medical School, 2005.

This pamphlet is an example of postwar mendicant literature—items printed and sold for the support of their authors—and illustrate some of the hardships faced by disabled veterans in later life.

Henry H. Meacham, a former carriage-maker in Massachusetts, joined the 32nd Massachusetts Volunteers; his arm was blown off by a shell near Petersburg in June, 1864. He printed and sold this pamphlet to make a living for himself and his ailing wife. In this account of his war experiences, Meacham says,

"As we were standing there, a shell came through one man and then exploded, taking my right arm off, and killing four of my comrades, making five lives destroyed and one wounded. I never expected to get home or even off the field, but I was bound to do all I could… I was at this time one mile from any surgical assistance, and walked that distance, while the blood was fast leaving me, notwithstanding I had bandaged the arm as tight as possible…. I was so weak as to be unable to walk, or hardly stand…. I had not long to wait before the surgeon came along, and at my earnest request, I was taken to the amputating room and placed on the table. This is the last that I remember until my arm was amputated. After I had fully come to my senses, I was conducted back to my bed on the ground, and there I remained during the night with my bloody clothes on."

The cover of the 1874 poem states, “The author of this book lost his arm in the discharge of his duties as Machinist on board the Demaly while conveying troops from Galloup’s Island to City Point, Va.”

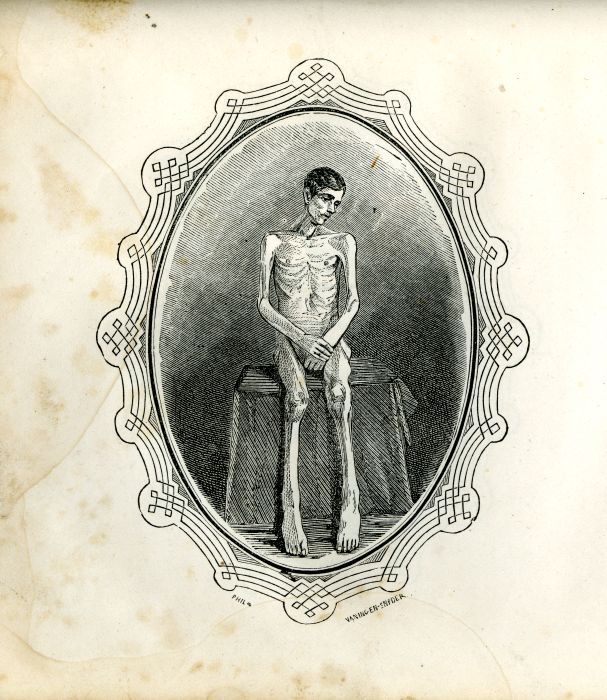

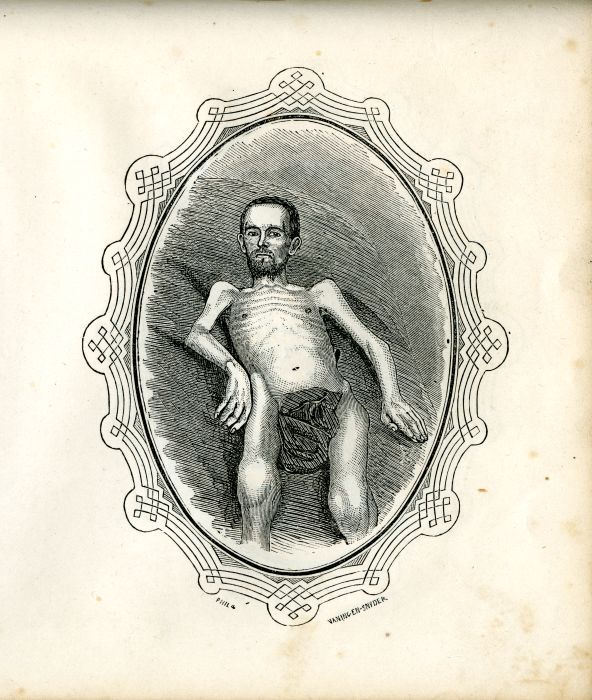

"Private John Q. Rose"

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, United States Congress

In the Senate of the United States, May 9, 1864 ... : Report of the Sub-Committee on Returned Prisoners,

[Washington : G.P.O., 1864].

Gift of George H. Jackson, Jr., M.D., to the Library of Harvard Medical School, 1929.

This report to the Senate outlines the treatment of Union prisoners of war by the Confederate forces at Belle Isle.

"Your committee, therefore, are constrained to say that they can hardly avoid the conclusion, expressed by so many of our released soldiers, that the inhuman practices herein referred to are the result of a determination on the part of the rebel authorities to reduce our soldiers in their power, by privation of food and clothing, and by exposure, to such a condition that those who may survive shall never recover so as to be able to render any effective service in the field."

The engraving depicts released prisoner Private John Q. Rose, admitted to the U.S. General Hospital in Annapolis. Private Rose died May 4, 1864.

"Private L. H. Parham"

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, United States Congress

In the Senate of the United States, May 9, 1864 ... : Report of the Sub-Committee on Returned Prisoners

[Washington : G.P.O., 1864].

Gift of George H. Jackson, Jr., M.D., to the Library of Harvard Medical School, 1929.

The engraving depicts released prisoner Private L. H. Parham, admitted to the U.S. General Hospital in Annapolis. Private Parham died May 10, 1864 “from effects of treatment while in the hands of the enemy.”

An estimated 30,000 Union soldiers and some 26,000 Confederates died in prisons during the course of the war.