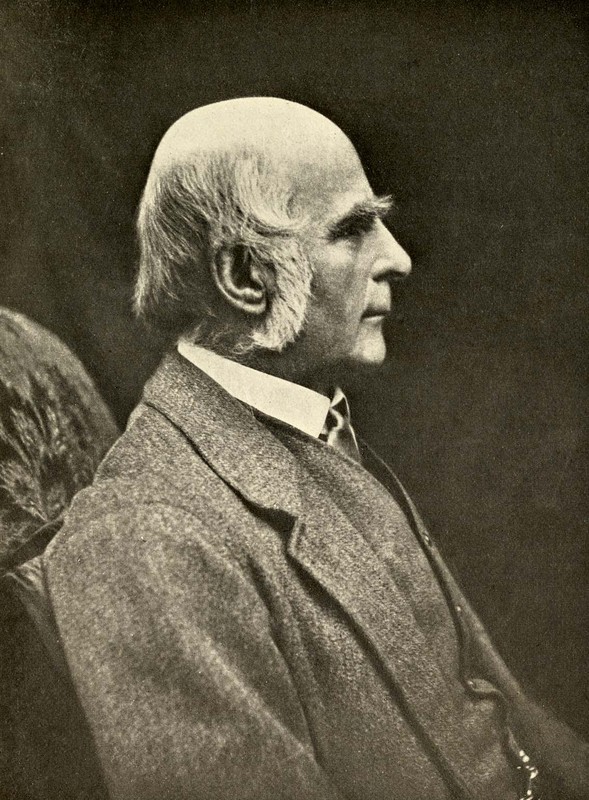

Sir Francis Galton

Eugenics has a certain historic starting point, and the founder of the movement is Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), a cousin of Charles Darwin. Working from a background in the Darwinian theory of evolution, Galton considered famous and talented intellectuals, artists, and athletes in relation to their families and progenitors and came to the conclusion that mental abilities and characteristics were inherited. He first proposed this idea in an article in 1865 and then expanded the idea into the monograph, Hereditary genius : an inquiry into its laws and consequences (1869), which documents his genealogical research. Galton also worked with photographs of prisoners to determine whether facial characteristics could be correlated to particular criminal tendencies. His work was complemented in some degree by Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909), whose L’uomo deliquente (1876) proposes that criminal tendencies were also subject to inheritance even as mental abilities were.

The very term “eugenics” (a neologism derived from Greek words meaning “well born”) was Galton’s formulation, and the word first appears in 1883, in his publication, Inquiries into human faculties and its development. He coins the term, defining it as “the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognisance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had.” Sir Francis Galton continued to work on eugenic concepts for the rest of his life.

On October 29, 1901, Galton delivered the Huxley lecture, “The possible improvement of the human breed under the existing conditions of law and sentiment,” in which he summarizes the aim of a national eugenics program, in both its positive and negative aspects: “The possibility of improving the race of a nation depends on the power of increasing the productivity of the best stock. This is far more important than that of repressing the productivity of the worst…. In seeking for the improvement of the race we aim at what is apparently possible to accomplish…. To no nation is a high human breed more necessary than to our own, for we plant our stock all over the world and lay the foundation of the dispositions and capacities of future millions of the human race.” The lecture was subsequently printed in Nature, the Reports of the Smithsonian Institution, and Popular science monthly.