Intubation: Endotracheal tubes

Endotracheal tubes

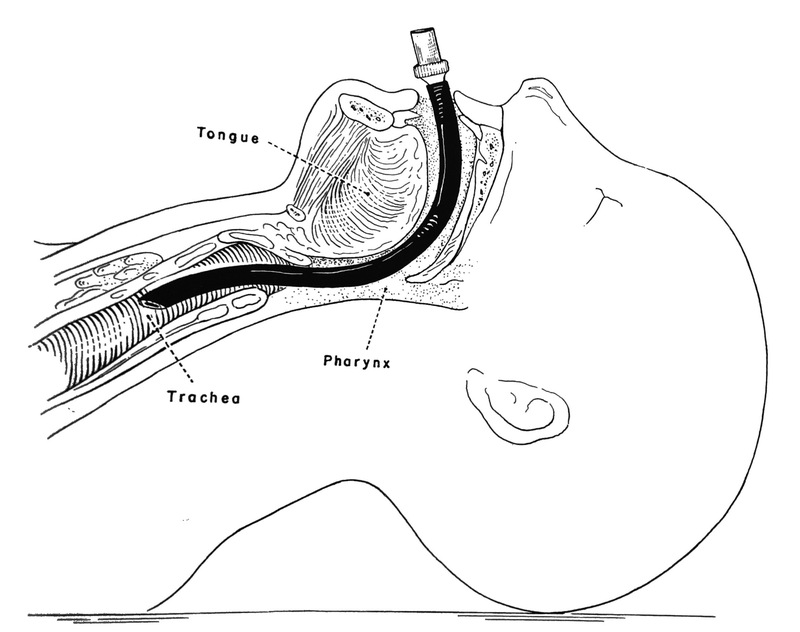

“Anesthesia can reduce the body’s ability to breathe normally. Anesthesiologists often make use of artificial airways, which are inserted over the tongue, to help maintain a clear passage through which the patient can breathe. Before endotracheal tubes came into common use, oral airways also provided a conduit for delivering anesthetic gases to the patient.” —Quote courtesy of the Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology, Schaumburg, Illinois.

Though the construction material has evolved from reusable rubber, to disposable plastic, intubation tools have not varied much in design since the Murphy style tube, introduced in the 1940s. The exception is the LMA (Laryngeal Mask Airway).

Obstetrical Anesthesia, Its Priciples and Practice, from which this illustration is sourced, was the first textbook devoted solely to obstetric anesthesia. It was written by Bert B. Hershenson, MD, Director of Anesthesia (1942–1956) at the Boston Lying-in Hospital (a BWH parent hospital). He was the first full-time director of an obstetric anesthesia service in the US.

Poe Throat Tube, circa 1920s (patented 1924)

James G. Poe, MD (1873-1935) designed this 5 inch long oral airway for use during operations as a prop to hold the mouth open. The center channel allows the passage of air. The two openings on the sides were for tubes used to introduce anesthetic gasses. The patient’s teeth held the airway firmly in place while the metal construction simultaneously prevented the teeth from crushing the tubes.

Murphy Style, circa 1950s and contemporary

In 1941, Dr. Francis J. Murphy (1900-1972), had some new design ideas for the simple endotracheal tube. He described both straight and curved tubes with holes on the side that act as emergency vents should the primary end opening become clogged. This improvement to patient safety was widely adopted and has ever since been known as the “Murphy eye.” Murphy also indicated that using high quality red rubber would afford needed flexibility but be strong enough to resist compression.

Note that these tubes have inflatable “cuffs” near the end. A cuff is inflated in the patient’s airway through the small side tube. Once inflated it helps to prevent aspiration and blocks air from flowing around the tube. Arthur Guedel’s rigorous experimentation in the late 1920s led to the practical, clinical use of cuffed tubes. Cuffless tubes are used in non-ventilated patients allowing them to cough and speak.

Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA), contemporary example

Designed as an alternative to an endotracheal airway, the LMA or “supraglottic” airway, was first introduced in 1988. It is an airway device that rests upon the vocal cords rather than passing through, presenting less risk of vocal cord damage.

An anesthesiologist will choose either an endotracheal tube or an LMA airway for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to, the type of surgery, duration of the surgery, type of ventilation required during the surgery, and characteristics of the patient, i.e., obesity, or potential aspiration risk.