Thomas Dwight

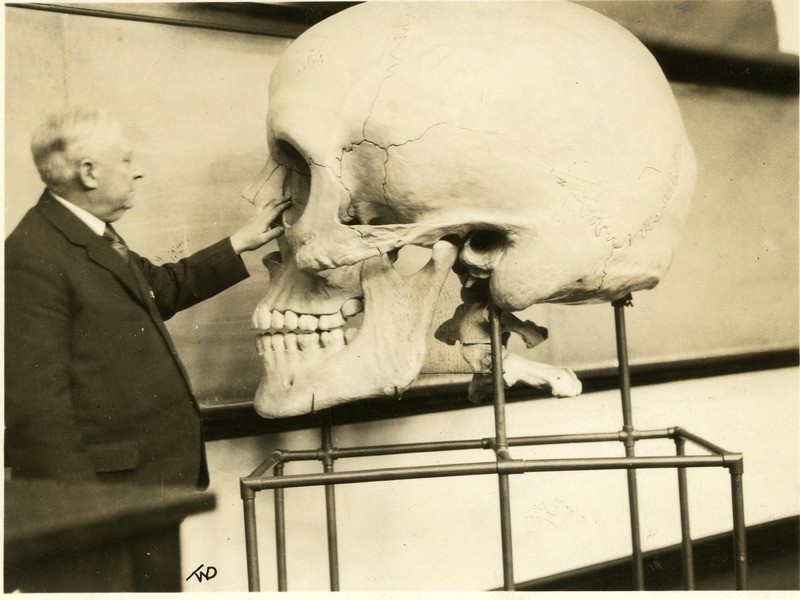

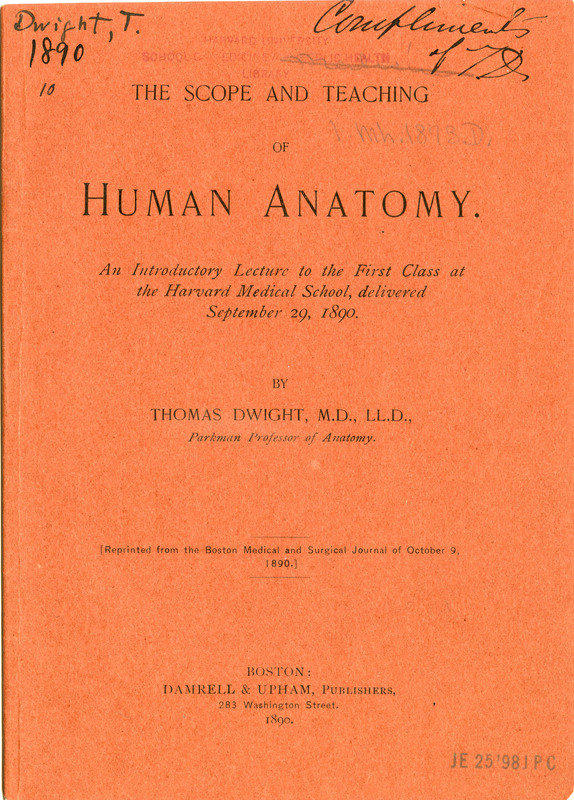

After Holmes’ resignation from teaching in 1882, a great-grandson of John Warren, Thomas Dwight (1843-1911), became the Parkman Professor of Anatomy, ushering in a new and dynamic phase of education and research. Dwight assessed the state of anatomical teaching at Harvard in a lecture in 1890, stressing the importance of lectures coupled with demonstrations, illustrating his points with bones or human subjects, if available, or with models and diagrams, as well as work in the dissection room. During this period, Dwight sponsored the creation of a collection of over twenty large-scale paper pulp models of the skull and bones of the body by naturalist and artist, James Henry Emerton (1847-1931), for use in his lectures. Dwight’s classes were divided into small groups for informal recitation sessions, with the object “of seeing things close to, of handling the specimens as much as possible, and of asking questions… making clear what any lecture may at times leave somewhat misty,” and he encouraged the use of boxes of bones which could be borrowed and studied by the students “very much as you would draw a book at the office of the circulating library.” Dwight also offered a course in advanced anatomy for second-year students and promoted the use of the Warren Anatomical Museum, particularly its collection of bones, dissected joints, frozen sections, and corrosion preparations, though he acknowledged with regret “that the museum has never been utilized as it should be as place for study. It is a place where much may be learned.”

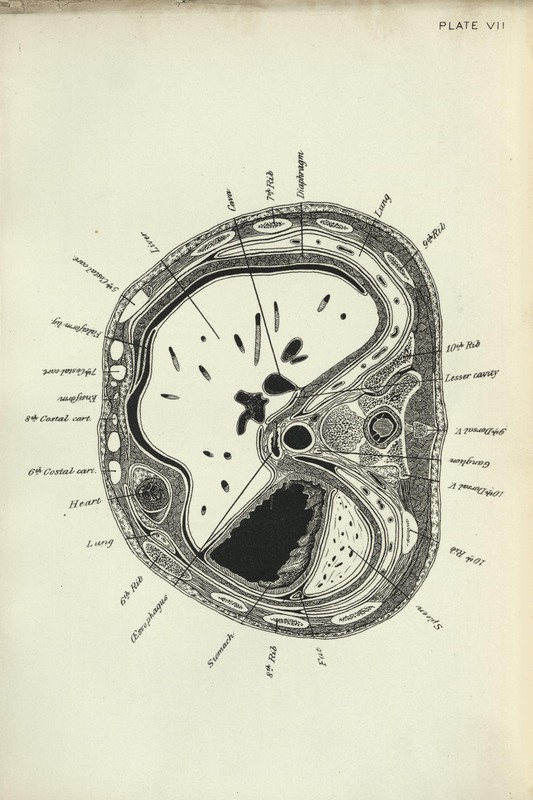

Dwight, while serving as Instructor in Topographical Anatomy and Histology, made these sections of a three-year-old child for use in his lectures at the Medical School in 1880-1881 and were some of the first frozen sections in use in this country. The plates are life-size. As part of the preface, Dwight includes his directions for making such specimens.

First, be very sure that the body, or part, to be frozen is in precisely the position you desire, and that there are no folds or indentations in the skin. I always use natural cold when possible. Weather much about zero (Fahrenheit) is unsatisfactory; but if the part is thoroughly chilled by several days' exposure to a pretty low temperature, a night of 10˚ may possibly finish it. Salt and ice, or snow, no doubt, will answer the purpose, but much time and patience are required…. The body should be frozen like a rock–so much so that the operator cannot tell whether he is cutting bone or muscle…. The sections should be made in a cold room, with a very sharp saw that has been chilled. When a section is cut, its surface is obscured by a thick half-frozen saw-dust, which is doubly thick if the freezing is not quite sufficient. It is wisest, if time allows, to remove this at once, which is done by pouring a little hot water over the section and brushing or scraping it off rapidly and carefully. This is a very delicate part of the process, and its successful performance has much to do with the beauty of the specimen. If it is to be kept, it should be laid on a piece of glass or wood, and placed at once, while still frozen, in cold alcohol.

This is a presentation copy from Dwight to Oliver Wendell Holmes.

By 1900, in addition to Dwight as full professor, the Department of Anatomy had an associate professor, demonstrator, instructor, and eleven assistants. First-year students were taught through lectures, recitations, practical exercises and dissections, and demonstrations; second-year students concentrated on frozen sections and living models; and there was even an elective fourth-year course based in the dissection room. Towards the end of his career, Thomas Dwight also instituted a course on anatomy using the X-ray and interpretation of radiological plates.

Thomas Dwight was also deeply concerned with the varied nature and provisions of anatomical laws throughout the country. In an article published in Forum in 1896, he asserted that:

The principle is to be laid down that such a body is, as it were, only loaned to science, and that it is to be treated with decency throughout the operation of dissection…. The examination being finished, the body is to be decently buried in a cemetery; if possible, in one of the creed of the deceased. Probably the nearest approach in America to this treatment of the remains prevails at Harvard. I like to boast that, for many years, not a single body has been received by the anatomical department for which I am not ready to give an account…. There is no wrong to the living, no insult to the dead, and the needs of science are met.