Medical Reform

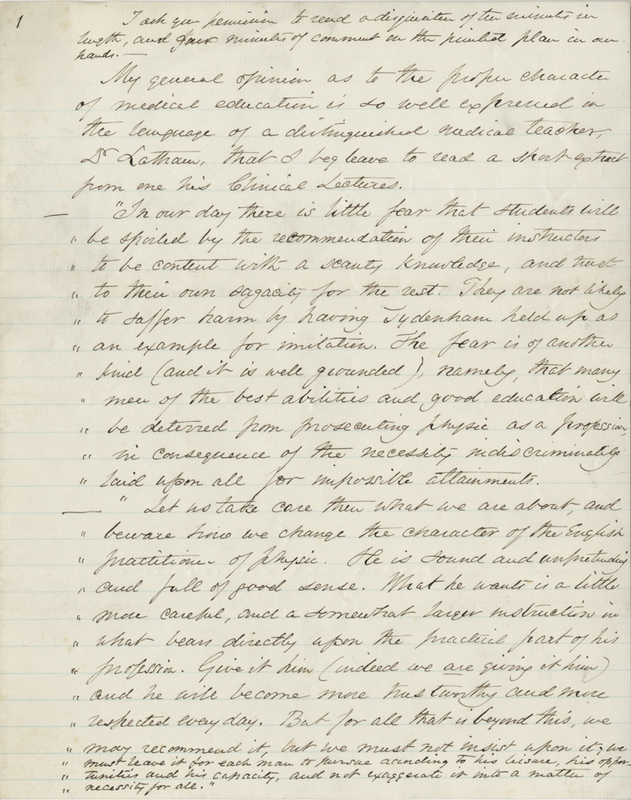

Despite Harvard’s renowned faculty members and array of courses, the students themselves in the mid-19th century were often poorly trained. Few of the matriculants had formal college degrees upon entering the school, the required course of study was short, and the medical examinations at the end were haphazard. It was the advent of President Charles William Eliot (1834-1926) in 1869, which brought about a complete revolution in the medical curriculum. Eliot faced resistance from the faculty but ultimately managed to institute a new set of statutes for the Medical School in 1870, insisting on more stringent entrance requirements. He also increased the size of the faculty, extended the medical course to three years with examinations throughout, and even began the academic year in September rather than November. Of these changes, Holmes said, "Our new President, Eliot, has turned the whole University over like a flapjack. There never was such a bouleversement as that in our Medical Faculty." This manuscript essay by Holmes, expressing his cautious views on the Eliot reforms (“I am ready for a step onward, perhaps for a stride, but not quite ready for a leap,”) was probably one presented to the Medical Faculty at its meeting on March 16, 1871, when the new plan of instruction was being debated.

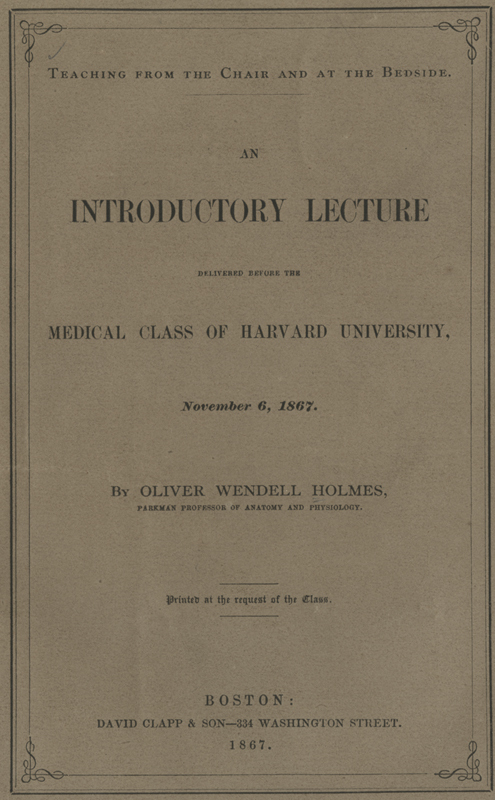

At the opening of the term and the beginnings of debate over educational reform at the Medical School, Holmes gave this address to the students, partly in defense of the summer term of practical instruction over the formal lectures of the winter. “The bedside is always the true center of medical teaching. Certain branches must be taught in the lecture-room, and will necessarily involve a good deal that is not directly useful to the future practitioner. But the over ambitious and active student must not be led away by the seduction of knowledge for its own sake from his principal pursuit. The humble beginner, who is alarmed at the vast fields of knowledge opened to him, may be encouraged by the assurance that with a very slender provision of science, in distinction from practical skill, he may be a useful and acceptable member of the profession to which the health of the community is entrusted.”

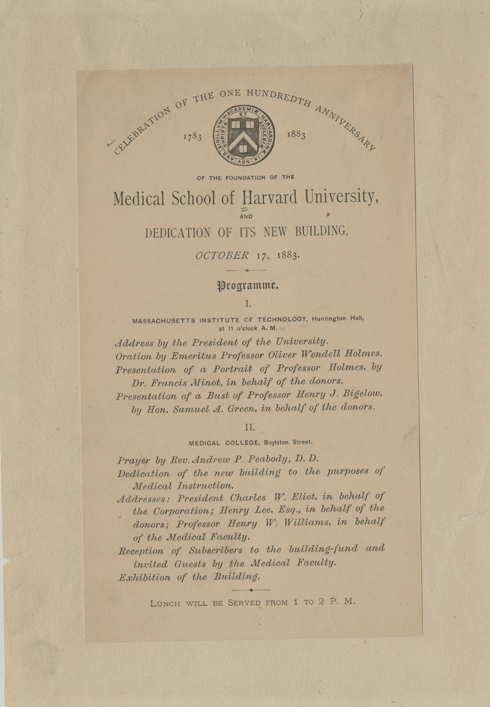

During the 1880s, Holmes was involved with the fund-raising appeals for the Medical School’s Boylston Street building. As part of the centennial celebration and dedication of the new building in 1883, he delivered this oration, tracing the history of medicine in Boston and Harvard Medical School from the Revolutionary War up to the present day.

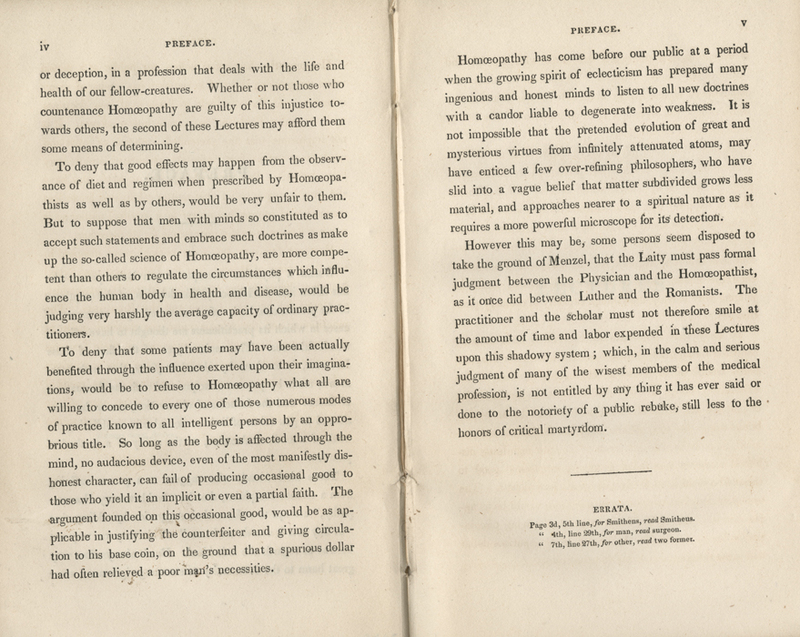

Holmes delivered this critical address on homeopathy to the Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge on February 16, 1842, and then published it with a companion lecture, "Medical delusions of the past," later that spring. Although Holmes would deal with homeopathy "not by ridicule, but by argument; perhaps with great freedom, but with good temper and in peaceable language; with very little hope of reclaiming converts, with no desire of making enemies, but with a firm belief that its pretensions and assertions cannot stand before a single hour of calm investigation," the lecture ignited a war of words in newspapers and pamphlets.

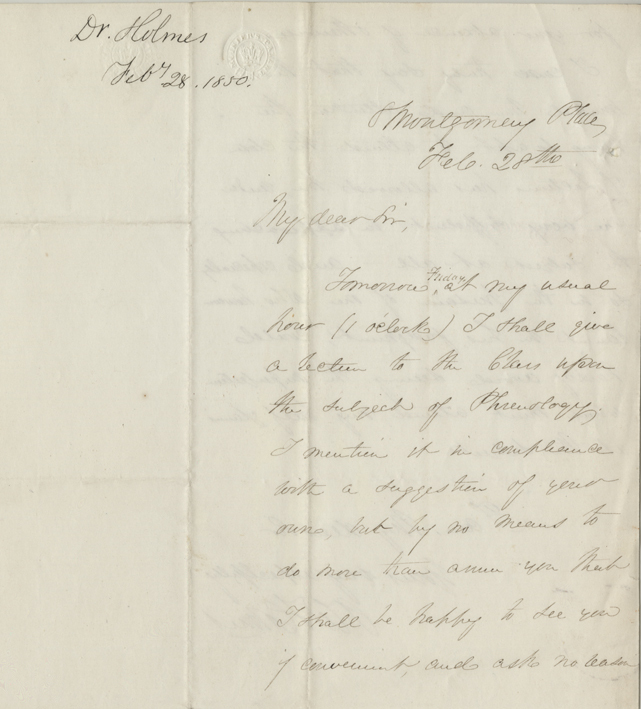

While Holmes' views on homeopathy are well attested, this letter to Dr. John Collins Warren (1778-1856) indicates he had at least some early interest in the concurrent phrenological movement. Holmes here invites Warren to attend his lecture on the subject at Harvard and modestly states, "I can truly say that the limited time and attention, which the hurry so apt to attend the close of lectures has allowed me, render me very diffident in approaching the subject at all, and especially so in the presence of one who, however lenient in his judgment, could hardly avoid seeing the imperfections which must attend my brief glance at the subject." In 1849, Warren had taken possession of the Boston Phrenological Society's collection of casts and skulls, including the skull of Johann Gaspar Spurzheim. That collection now resides with the Warren Anatomical Museum.

By 1861, however, Holmes’ views on phrenology were set. He said, “I am not one of its haters; on the contrary, I am grateful for the incidental good it has done…. Yet I should not have devoted so many words to it, did I not recognize the light it has thrown on human actions by its study of congenital organic tendencies. Its maps of the surface of the head are, I feel sure, founded on a delusion, but its studies of individual character are always interesting and instructive.”

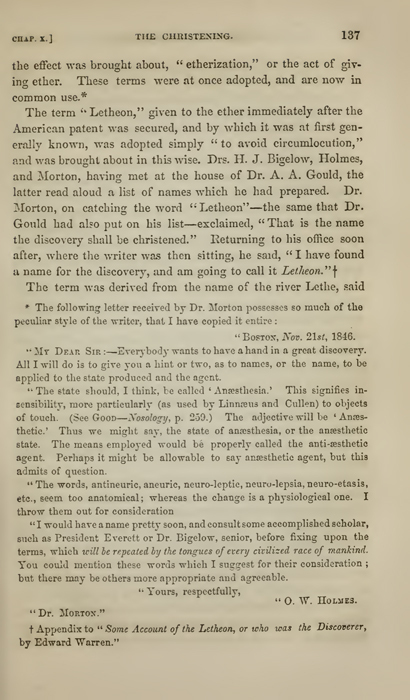

Commissioned by William T. G. Morton, Trials of a public benefactor attempts to provide support for his claim to precedence in the discovery of ether anesthesia. Here, as part of the story, Oliver Wendell Holmes coins the term in a letter to Morton written on November 21, 1846, shortly after the first public demonstrations at Massachusetts General Hospital. Holmes wrote, “Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give you a hint or two, as to names, or the name, to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think, be called ‘Anæsthesia.’ This signifies insensibility, more particularly (as used by Linnæus and Cullen) to objects of touch…. The adjective will be ‘Anæsthetic.’ Thus we might say, the state of anæsthesia, or the anæsthetic state…. I would have a name pretty soon, and consult some accomplished scholar, such as President Everett or Dr. Bigelow, senior, before fixing upon the terms, which will be repeated by the tongues of every civilized race of mankind.” Holmes' personal copy contains contains a presentation inscription to him from William T. G. Morton.