Puerperal Fever

Beyond his years devoted to teaching and anatomical dissection, Holmes’ reputation in medicine rests on his early research into the question of the contagiousness of puerperal fever. During the summer of 1842, the Boston Society for Medical Improvement, a scientific organization of which Holmes and many of his friends from his European sojourn were members, began to turn its attention to the matter of puerperal fever, a form of peritonitis afflicting women in the days after childbirth and often proving fatal.

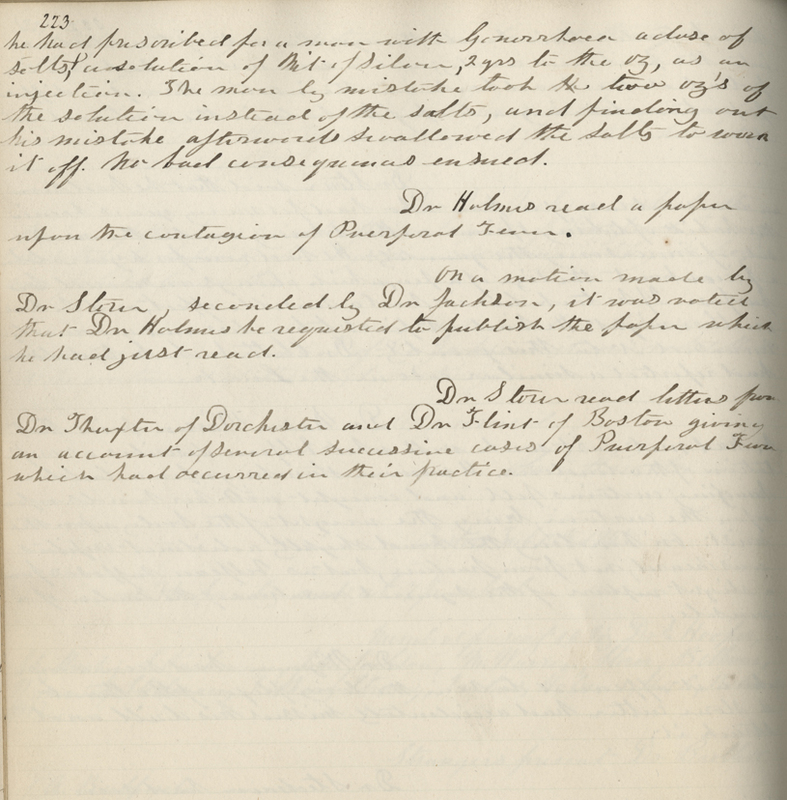

Following reports of an outbreak of cases in Salem, Walter Channing’s presentation of thirteen fatal cases in Boston in June, and news of the illness and deaths of some physicians and students, J. B. S. Jackson “asked the opinion of the Society as to the contagion of puerperal fever and the probability of physicians communicating it from one patient to another.” Holmes proceeded to research the matter through case reports and medical literature at the Boston Athenaeum and delivered his findings at a meeting of the Society held on February 13, 1843.

Holmes concluded that puerperal fever was not only contagious, but “obstetricians, nurses, and midwives were active agents of infection, carrying the dreaded disease from the bedside of one mother to that of the next." Following his presentation, Holmes first published his findings in The New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery, in April 1843. The article was also reprinted in pamphlet form.

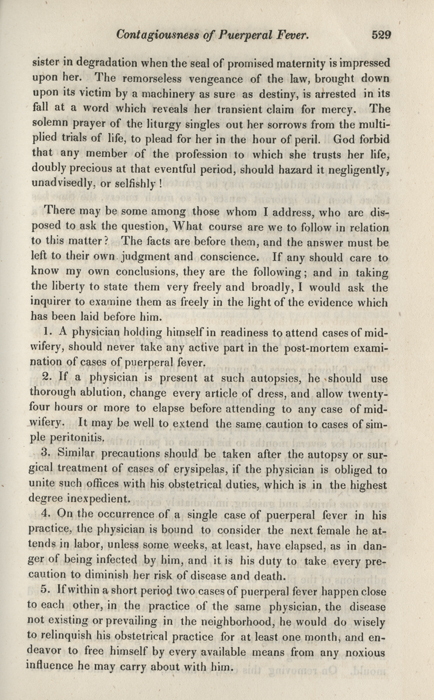

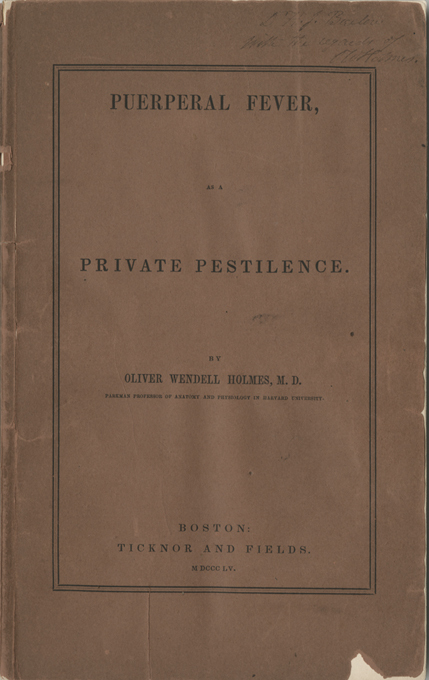

There was initially a great deal of resistance and even hostility to Holmes’ findings, particularly from two noted Philadelphia obstetricians, Charles D. Meigs and Hugh Lenox Hodge. In 1855, Holmes reprinted the original article as Puerperal Fever, as a Private Pestilence, containing a lengthy introduction along with additional cases and evidence to support his initial assertions. “I do not know,” Holmes said, “that I shall ever again have so good an opportunity of being useful as was granted me by the raising of the question which produced this essay. For I have abundant evidence that it has made many practitioners more cautious.”

Fifty years after the first puerperal fever essay, Holmes wrote of it to James Read Chadwick, “I have been long out of the way of discussing this class of subjects. I do not know what others have done since my efforts; I do know that others had cried out with all their might against the terrible evil before I did, and I gave them full credit for it. But I think I shrieked my warning louder and longer than any of them, and I am pleased to remember that I took my ground on the existing evidence before the little army of microbes was marched up to support my position.”

This rare photograph depicts physicians (standing, left to right) Charles Eliot Ware, Robert William Hooper, Le Baron Russell, Samuel Parkman, (seated, left to right) George Amory Bethune, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Samuel Cabot, Jonathan Mason Warren, William Edward Coale, and James Browne Gregerson, near the period of Holmes’ presentation on puerperal fever.